Tuesday February 21, 2017

By Lisa Laventure

Asylum-seekers face risks crossing South and Central America but worry about travelling through U.S.

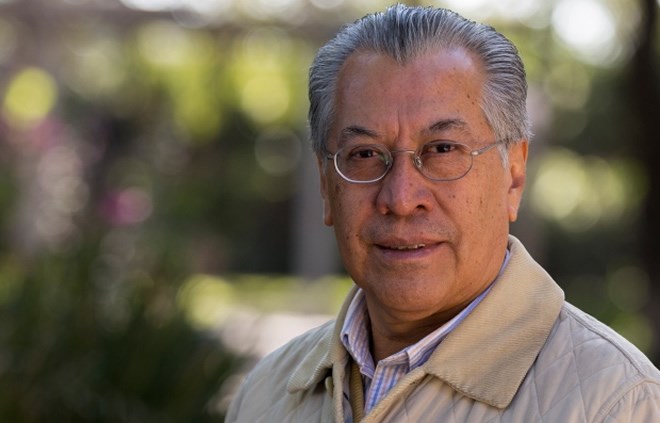

Abdikadir Ahmed Omar, of Somalia, travelled from the West African nation of Togo to Brazil and then made a three-month trek across nine countries in South and Central America. (Marc Robichaud/CBC)

The threats against his life had been coming by phone for months.

But it was only after two men armed with AK-47 assault rifles shot up the home he shared with his wife and young child that Abdikadir Ahmed Omar says he knew he would be forced to flee his home country of Somalia.

His role as a human rights activist — and occasionally as a translator for media outlets, including once for the CBC — had put him on the radar of the al-Qaeda-linked militant group al-Shabaab.

He says he reported the threats to the police commissioner in his home city of Kismayo.

"But if Shabaab wants to kill you, they will," says Ahmed Omar, 30.

He says police told him there was no way he could escape the threats and they couldn't give him protection.

"The only option was for me to leave."

What came next was a harrowing journey beginning in August 2016, Ahmed Omar says, when he fled Nairobi in an attempt to reach what he calls the last remaining sanctuary for migrants fleeing violence, political instability or famine: Canada.

He is among a growing number of asylum-seekers looking to Canada for sanctuary, according to those who are involved in helping migrants.

In the past, many like Ahmed Omar would have been targeting the U.S. as their final stop, but that's changed in the wake of U.S. President Donald Trump's policies on immigration.

CBC News interviewed more than two dozen migrants in Mexico City and Tapachula, on the Mexico-Guatemala border. The young men and women had left home countries of Somalia, Ghana, Guinea-Bissau, Ethiopia, Eritrea, India, Bangladesh, Nepal and Yemen.

They travelled by foot, bus, boat and train through Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Panama, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala and Mexico — a journey that takes three to five months and costs upwards of $20,000 US per person.

A map showing the approximate route many migrants take - with the help of smugglers - to get to Canada. (CBC)

Many began their journeys with Canada in mind. Others decided to head to Canada instead of the U.S. after, in their assessment, Trump effectively closed the American border to them.

The issue has gained urgency in Canada in recent months as dozens of migrants have shown up hungry, cold and exhausted on the Canadian side of the border in Manitoba, Quebec and other provinces after having snuck across the U.S-Canada border on foot in the final, precarious leg of their journey.

No European option

For Ahmed Omar, the Mediterranean Sea route to Europe wasn't an option, with borders increasingly tightened in response to the migrant crisis there. So he boarded a flight to the West African nation of Togo with an alternative route in mind.

Ahmed Omar says he went from West Africa to Brazil and then made a three-month trek across nine countries in South and Central America and along a well-trodden migration route north toward the U.S. Now, he says, he's stranded in Mexico.

"I am a black man, I am a Muslim and I am a Somali. So in three ways, it is not possible for me to go to the United States," Ahmed Omar told CBC News in an interview in Mexico City.

He fears the risks travelling through the U.S. to cross into Canada could entail. His humanitarian visa allows him to stay in Mexico City for only a few weeks.

Along the way, he encountered multiple groups of Somalis making the same voyage — including Guled Abdi Omar, 27.

Guled Abdi Omar, 27, says he lived in Dadaab, the world's largest refugee camp, in eastern Kenya, until he fled three years ago after being approached by recruiters from al-Qaeda-linked militant group al-Shabaab. (Marc Robichaud/CBC)

Abdi Omar's family fled Somalia in 1992, when he was two years old, and they've been living in Dadaab, the world's largest refugee camp, in eastern Kenya. He fled the camp three years ago, after being approached by al-Shabaab recruiters, then decided to find a country of asylum where he could bring his family.

Like Ahmed Omar, Abdi Omar felt he had few options. His brother had recently migrated to Australia, but said the boat voyage was unbearably dangerous. He urged Abdi Omar to escape to Central America.

"He said: 'I don't want you to die; go to Canada,'" Abdi Omar told CBC News. "I can't go back [to Somalia]. I am a man with no land, no country."

Willing to be detained

Abdi Omar says his plan was to enter the U.S. through a legal border crossing. He says he expected to be detained and ultimately denied asylum, but if released would have continued north.

"I want Canada, but there is no way I can go through America to Canada illegally. This is the only way."

Many of the migrants who spoke to CBC News say they consider travelling through the U.S. to be as risky as the trip through South and Central America.

And it is a perilous route. Migrants spoke of dangerous deals with human smugglers — called coyotes — as well as assaults, detentions and robberies.

Ahmed Omar, right, met other Somali migrants in Mexico City who'd made the same journey he did. Here he's pictured with Mustafa Adam, 19, left, and Abdiaziz Ahmed, 29, centre. ( Marc Robichaud/CBC)

But often cited as the most treacherous part of the trip was crossing the Darien Gap — a large swath of jungle connecting Panama to northern Colombia that is inhabited by poisonous snakes and paramilitary groups.

The trip, by foot and boat, takes five to seven days. Migrants reported walking past dead bodies.

CBC News spoke to a young Ghanaian man and woman who said they completed the trek with their seven-month-old baby over five days, abandoned by smugglers they'd paid, with no food or clean water.

"When we were in the jungle … sometimes, I just feel like I could go back to Dadaab," says Abdi Omar.

'Canadian dream'

In recent weeks, an increasing number of refuge-seekers hoping to claim asylum in Canada have crossed the border by foot, mostly in Quebec and Manitoba and often in dangerously cold conditions.

Ahmed Omar says the freezing dash across the Canada-U.S. border is simply the last necessary step to reach Canada by any means necessary via a migratory route used for decades by Central American migrants attempting to flee violence in countries such as Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala.

Rodolfo Casillas, migration specialist at the Latin American Faculty of Social Sciences in Mexico City, says Canada is 'a country of great hope for many migrants.' (Marc Robichaud/CBC)

The American dream is transforming into the "Canadian dream," says Rodolfo Casillas, a migration specialist at the Latin American Faculty of Social Sciences in Mexico City.

Casillas says he was invited by the Canadian Embassy in Mexico City to discuss the migrant situation with former foreign affairs minister Stéphane Dion.

The government expressed "great concern" about the trend, but, Casillas says, little knowledge of the reality on the ground.

"Canada is going to have to be very practical, but look for ways to honour its humanitarian tradition, which is one of the greatest distinctions it has, and that makes it a country of great hope for many migrants.”

Ahmed Omar says refugees have a lot to contribute. He points to federal Immigration Minister Ahmed Hussen, a refugee from Somalia, as a prime example of the contributions refugees can make.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau "doesn't compromise the security of Canada.

At the same time, they have policies in place to help the refugees," Ahmed Omar says.

"We will never be a burden; we will be a success story. I am 100 per cent sure," says Ahmed Omar.

When asked if, given the cold climate, Abdi Omar would try to cross into Manitoba by foot, he says he would take the risk.

"There is no other option. I either die or survive — those are the two options I have," he says. "And I am willing to do that for the sake of my parents and my wife."