Thursday November 20, 2025

By Mohamed Mukhtar Ibrahim

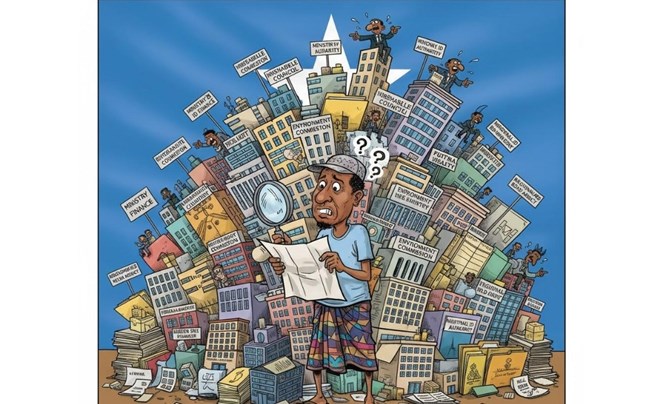

Somalia is drowning in its own institutions. What began as an effort to rebuild governance after a decade of collapse has evolved into a sprawling, expensive bureaucracy that the country can no longer sustain. Across the federal government and member states, more than 340 government institutions now exist — many with overlapping mandates, redundant structures, and ballooning administrative costs.

This article builds on my earlier piece titled “Do We Need 999 Representatives, 8 Presidents, and 454 Ministers?” — which questioned the size and cost of Somalia’s political leadership. While that article focused on the growing number of elected and appointed officials, this follow-up turns to the institutions themselves—the machinery of government that underpins political operations.

Somalia’s federal government currently comprises 70 public institutions, encompassing ministries, departments, and agencies (MDAs). Of these, 67 institutions are included in the national budget, while three, such as the National Higher Education Committee, are set to be incorporated in the upcoming financial year. Each entity requires operational funding for salaries, facilities, vehicles, maintenance, communications, per diem expenses, and foreign travel. Given Somalia’s limited domestic revenue and its continued dependence on external donor funding, sustaining such a large administrative structure has become one of the country’s most pressing governance and fiscal challenges. The issue extends beyond quantity: overlapping mandates, weak inter-agency coordination, and a misalignment between government size and national economic capacity have eroded institutional efficiency.

Somalia’s federal system compounds this challenge. The country has yet to reach an explicit agreement on how powers and responsibilities should be divided between the federal and state governments. Moreover, the unresolved question of Somaliland’s political status continues to complicate the broader federal arrangement, leaving the nature of the Somali state itself — whether it should remain federal or pursue alternative frameworks — open to debate. In the absence of this clarity, Federal Member States have replicated nearly all the institutions found in Mogadishu, including those of the presidency, parliament, finance, education, health, interior, and security. Each state now maintains a sizable bureaucracy of its own: Somaliland operates 63 institutions, Puntland 48, Northeastern 31, Galmudug 34, Southwest 36, Jubaland 34, and Hirshabelle 32 — demonstrating the extensive duplication that has emerged within Somalia’s federal system. When combined with the 67 federal institutions, Somalia now operates more than 340 government institutions nationwide, illustrating the scale of bureaucratic expansion across the federal system. The Comparative Structure of Government Institutions presented in the table below illustrates how the Federal Government, Somaliland, and Puntland each maintain parallel administrative frameworks that often duplicate ministries and agencies across similar sectors.

The proliferation of parallel entities not only stretches limited fiscal resources but also deepens institutional fragmentation. For example, on 6 November 2025, the Puntland Council of Ministers approved the establishment of the Puntland Identification and Registration Authority, set to become operational on 1 January 2026, despite the existence of a federal National Identification Registration Authority. This development highlights the growing divergence among member states and raises concerns about policy coherence, data integration, and the integrity of national systems, including identity management systems.

This duplication has profound governance implications. It dilutes accountability, inflates administrative costs, and fuels political competition over mandates and resources. Rather than reinforcing governance, Somalia’s institutional expansion has contributed to inefficiency, confusion, and a decline in public trust in state structures.

Financial data reinforce this picture. According to the Somali Public Agenda’s analysis of the Federal Government of Somalia’s 2025 budget, administrative spending continues to dominate public expenditure—$427.7 million, up from $382 million in 2024 —accounting for 32.4% of the total budget. Alarmingly, these administrative costs nearly match the government’s total domestic revenue, reflecting a severe fiscal imbalance that leaves minimal space for investment in essential public services such as health, education, and infrastructure.

This problem is mirrored at the regional level. The Somaliland 2025 Budget Analysis by the Institute for Strategic Insights and Research (ISIR) reveals that governance remains a significant area of expenditure, accounting for $69.6 million, or 19% of the total spending. The total collective administrative costs across federal and state governments leave little room for investment in essential public services such as health, education, and infrastructure.

Somalia thus stands at a critical crossroads. The challenge is no longer just about political will or institutional design, but also about affordability and functionality. Can a state with modest domestic revenue and high donor dependency continue to sustain such an expansive bureaucratic system?

Meaningful reform must aim for a leaner, better coordinated, and fiscally sustainable government structure. This requires the following steps:

- Initiate an inclusive national dialogue to address unresolved political settlement issues — including the status of Somaliland, the nature of the Somali state, and the equitable distribution of power and resources. A clear political consensus is the foundation for any sustainable governance reform.

- Conclude negotiations between the Federal Government and FMSs on the Exclusive, Concurrent, and Residual powers list to define responsibilities and eliminate overlapping mandates clearly.

- Merge or dissolve agencies with near-identical mandates (e.g., combining the functions of the Ministries of Ports and Air Transport or other overlapping entities) to reduce recurrent costs and improve operational efficiency.

Without such a shift, the state risks remaining politically divided, overextended, inefficient, and perpetually dependent on external aid to fund its oversized apparatus.

Comparative Structure of Government Institutions: Federal Government, Somaliland & Puntland